Emerging Use of POCUS- Point Of Care Ultrasound

- Ally Lobello

- May 16, 2023

- 4 min read

Integrating Point of Care Ultrasound into Internal Medicine curriculum has been a hot topic as of late. Point of Care Ultrasound also known as POCUS is defined as beside ultrasound performance by treating physician as an adjunctive to the traditional clinical assessment. POCUS has been referred to as a “fifth pillar” of the physical exam in addition to the classic inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.

The creation of portable ultrasound machines has made this modality more readily available at bedside on the wards. Traditionally, ultrasound was mostly utilized by radiologists, but recently there has been a push for bedside ultrasounds to answer focused questions about presence or absence of specific findings.

Integration of POCUS as a pillar of the traditional physical exam has allowed for earlier and more accurate diagnoses at the bedside. Another advantage is how innocuous POCUS is; patients are not exposed to unnecessary ionizing radiation or contrast. Ultrasound machines are relatively cheap and easy to attain, making POCUS a valuable tool for more remote or rural care centers. Compared to other imaging modalities, use of POCUS yields rather immediate results. Of note, data has shown that residents have been able acquire satisfactory ultrasound skills for kidney pathology such as hydronephrosis and renal cysts with as little as 5 hours of training.[1] Through the years, there has been significant evidence for supplementation of the physical exam with POCUS.

Beginning in 2004, a randomized controlled trial using ultrasound to assess nontraumatic hypotension in ED patients proved its accuracy in correctly diagnosing shock, increasing rates of accurate diagnosis from 50% to 80% 2. The study sampled 184 patients older than 17 who presented with vitals consistent with shock agreed upon by 2 independent clinicians. Patients were randomly split into 2 groups; each group received standard of care, and one group additionally received POCUS at 15 minutes. It was found that goal-directed point of care ultrasound narrows down differentials for unknown causes of hypotension in the ED. [2]

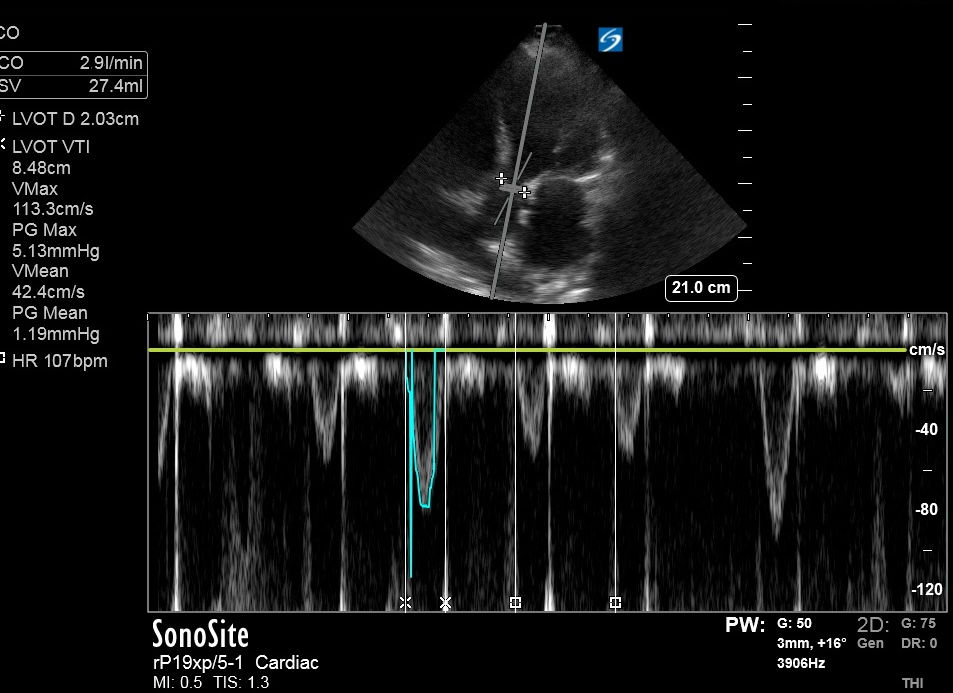

In 2010, the RUSH (rapid ultrasound in shock and hypotension) protocol was introduced which combined echocardiogram, lung, Inferior Vena Cava, and peritoneal views.[3] RUSH was found helpful in differentiating various types of shock allowing for optimal management. POCUS has become an essential component in the examination of patients presenting with undifferentiated hypotension and shock-like signs. Diagnosis and management in shock is notoriously difficult given the complexity of the disease process itself. The first portion of RUSH protocol consists of limited cardiac ultrasound to visualize the pericardial sac, contractility of the left ventricle, and relative size of the ventricles. Following assessment of the heart, inferior vena cava as well as lung, pleural, and abdominal cavities assessment should be done. Lastly, clinicians should assess thoracic/abdominal aorta as well as femoral and popliteal veins.

A 2018 study in the UK investigated the use of POCUS as a mainstay of evidence-based medicine. [4] It was initially thought that the ultrasound beam may not be particularly useful in assessing the lung parenchyma for causes of respiratory failure. This was found to be untrue. With a group of 260 ICU patients with respiratory failure as primary diagnosis point of care lung and deep venous ultrasound were performed and interpreted. The interpretation of these results was found to have a diagnostic accuracy of 90.5% which significantly surpasses other methods such as auscultation and chest radiography.

A 2020 study investigated the effect of POCUS on morbidity and mortality of cases in the emergency room. A retrospective study was done which looked at outcomes of 75 Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) cases presented by PGY4 ER residents. [5] It was found that in 45% of these cases, early intervention of POCUS could have likely prevented the morbidity and mortality. When dealing with cardiac or respiratory complaints especially, POCUS can be monumental. The study found that POCUS had potential to catch missed diagnoses, decrease time to appropriate treatment, and triage patients to higher level of care if necessary. Some of the challenges with POCUS include proper technique, accurate interpretation, and clinical judgement regarding which patients should receive it. In this study, there were 7 cases in which incorrect use of POCUS could have contributed to poor patient outcomes. [5] For example, there was one case in which a patient presented with cellulitis which has progressed to necrotizing fasciitis. The POCUS results correctly identified the soft tissue edema present but failed to notice the subcutaneous air present.

To prevent subpar use of POCUS, more ultrasound curriculum can be implemented in residency programs. A 2020 study assessed interns’ barriers to POCUS training, one of those being lack of time in residency. 74% of the interns who participated agreed that POCUS in an essential skill, yet only 22% has received any training in POCUS as a medical student. [7] It is important to begin integrating POCUS into medical school and residency curricula to expand its utilization and hopefully improve outcomes for patients.

About the author:

Aly Lobello is a third year medical student from Slidell, LA. She is planning on pursuing internal medicine. In her free time, she enjoys baking, hanging out with her cat Belle, and spending time outdoors.

References

1. Caronia J, Panagopoulos G, Devita M, Tofighi B, Mahdavi R, Levin B, Carrera L, Mina B. Focused renal sonography performed and interpreted by internal medicine residents. J Ultrasound Med. 2013; 32: 2007-2012. CrossRef PubMed

2. Jones AE. Tayal VS. Sullivan DM. Kline JA. Randomized, controlled trial of immediate versus delayed goal-directed ultrasound to identify the cause of nontraumatic hypotension in emergency department patients. Crit Care Med. 2004 ;32:1703–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Perera P, Mailhot T, Riley D, Mandavia D. The RUSH exam: Rapid Ultrasound in SHock in the evaluation of the critically lll. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010 Feb;28(1):29-56, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2009.09.010. PMID: 19945597.

4. Smallwood, N., & Dachsel, M. (2018). Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS): unnecessary gadgetry or evidence-based medicine?. Clinical medicine (London, England), 18(3), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.18-3-219

5. Goldsmith, A. J., Shokoohi, H., Loesche, M., Patel, R. C., Kimberly, H., & Liteplo, A. (2020). Point-of-care Ultrasound in Morbidity and Mortality Cases in Emergency Medicine: Who Benefits the Most?. The western journal of emergency medicine, 21(6), 172–178. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.7.47486

6. Abhilash Koratala, Deepti Bhattacharya, and Amir Kazory.Helping patients and the profession: Nephrology-oriented point-of-care ultrasound program for internal medicine residents. 2019; 91: 321-322. doi: 10.5414/CN109652.

7. Jarwan, W., Alshamrani, A. A., Alghamdi, A., Mahmood, N., Kharal, Y. M., Rajendram, R., & Hussain, A. (2020). Point-of-Care Ultrasound Training: An Assessment of Interns' Needs and Barriers to Training. Cureus, 12(10), e11209. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.11209

Comments