ICUCase#2 : Visual evidence of diuretic resistant volume overload through VEXUS

- Neev Patel

- Apr 4, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Jul 23, 2024

A 54-year-old male with a history of heart failure with reduced EF (EF 30%), coronary artery disease post-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), hypertension, diabetes, and obesity presented with shortness of breath. On physical examination, prominent jugular venous distention (JVD), diffuse bilateral crackles, and 3+ pedal edema were noted. Notably, the patient did not have any known hepatic or renal disease.

The patient was admitted to the Cardiac ICU for the management of acute-on-chronic heart failure.

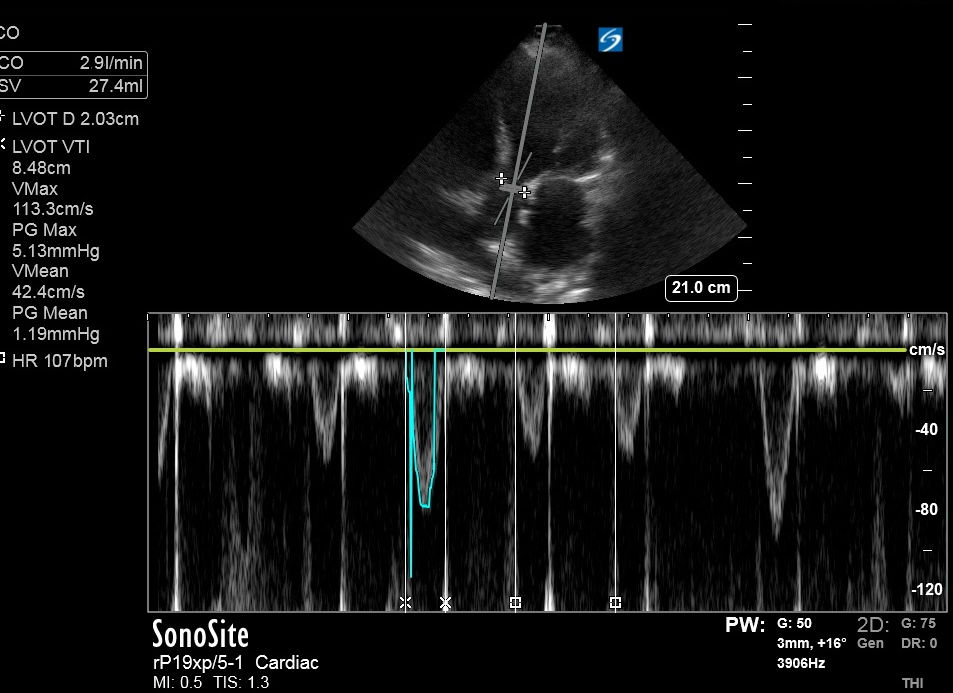

Upon admission, VEXUS was performed, yielding the following results:

( Reference table with waveforms and grading available at the bottom of this blog.)

1. Inferior vena cava (IVC): 3.51 cm and plethoric

2. Hepatic vein Doppler:

It is not possible to provide an accurate comment without live EKG tracing to identify ardiac cycles. However, based on morphology, it is likely that both the systolic and diastolic waves are downward, making it less likely to be S waver reversal (severely abnormal morphology).

3. Portal vein Doppler:

The pulsatility of the portal vein is greater than 50%, indicating a severely abnormal pattern. Normally, the portal vein's pulsatility is less than 30%.

It is interesting to note that cardiac pressures can easily transmit to the hepatic vein and affect its pulsatility. However, the flow in the portal vein varies minimally with cardiac cycles because the pressure variations are dampened by hepatic sinusoids, which connect the portal vein with the hepatic vein. In individuals with severe volume overload, the sinusoids aslo become congested, leading to the transmission of cardiac pressures from the inferior vena cava and hepatic vein to the portal vein. This results in increased pulsatility, as observed here.

4. Interlobar renal veins:

It demonstrated discontinuous monophasic flow, indicating that flow only occurs during diastole when cardiac relaxation allows for the emptying of central veins in the right heart. This absent flow in systole here is due to volume overload and increased CVP. Normally, renal veins exhibit continuous monophasic flow during both systole and diastole.

Hospital course:

For decongestion therapy, intravenous Lasix (furosemide) was initiated. The patient did not respond adequately to Lasix doses, even with uptitration to 160 mg doses. Subsequently, a Lasix drip was started at a rate of 10 mg/hr, along with metolazone 10 mg q12h, resulting in diuresis. Over the course of 3 days, a net negative fluid balance of 5 L was achieved.

On day 4, a repeat VEXUS was performed, revealing the following changes:

1. IVC: 2.8 cm, < 50% pulsatile

2. Hepatic vein doppler:

Compared to the previous finding, flow velocities have decreased, while the waveforms appear to be similar in morphology. Once again, two negative waveforms can be observed, indicating that S wave reversal is unlikely.

3. Portal vein (PV) doppler:

It has now returned to a normal pulsatility level of less than 30%.

4. Intralobar renal vein Doppler (IRVD):

It has now become continuous, although it exhibits a biphasic pattern instead of the normal monophasic continuous pattern. This demonstrates the alterations in flow pattern due to mild congestion.

On day 5 of the hospital course, successful transition to oral diuretics was achieved, and the patient was safely discharged home on the following day.

Discussion:

It is fascinating to observe rapid changes in bedside ultrasound following medical intervention.

A study with 217 patients published in JACC: Heart Failure evaluated acute heart failure patients upon admission using VEXUS to investigate the correlation between the severity and prognosis of heart failure exacerbation.

Interestingly, it was found that severely abnormal renal Doppler findings were associated with reduced diuretic efficacy and a higher incidence of diuretic resistance. Physiologically, increase in CVP leads to increase in renal venous pressure because of which the pressure gradient between renal artery and vein is decreased, leading to decreased GFR and hence diuretic resistance! This finding was also observed in this case!

Furthermore, intravascular expansion resulted in a significant blunting of renal venous flow before a substantial increase in cardiac filling pressures was demonstrated. If this finding is confirmed in a study with a larger sample size, it could potentially revolutionize early assessments by offering higher sensitivity through a noninvasive method!

To summarize findings:

For reference: VEXUS grading and patterns

Author:

Neev Patel, MD

Comments